In recent posts, we have approached the problem of the outlook for interest rates by outlining the questions that surround the potential growth rate of the U.S. economy. It is established that this rate is heavily influenced by conditions in the labor market. New workers are joining the labor force at a slower pace than in the past, and a smaller proportion of people who could work are working.

We’re not alone in considering the growth in the labor force and the willingness of people to work to be critical concerns. These concerns focus the debates at the Fed.

The Fed may see its credibility at stake

It is important to remember that the Fed is an institution that depends to a large extent on its credibility with the markets. While it is plain to see Fed policy come under criticism in the news media, members of the Fed also have ongoing dialogues with leaders of the markets, the banking community, and academic economists. These are the professional communities where members of the Fed serve portions of their careers.

The Fed also has an institutional memory and recalls the criticism it took in the 1970s, when inflation soared out of control. Many in the business community continue to fault the Fed for its reactions to events such as the energy supply shocks of the 1970s and the changing character of the labor market.

Past mistakes influence the Fed’s current views on the labor market

The Fed is carefully studying labor force dynamics right now because many of its critics believed the Fed misunderstood what happened in the 1970s, and therefore adopted the wrong policies.

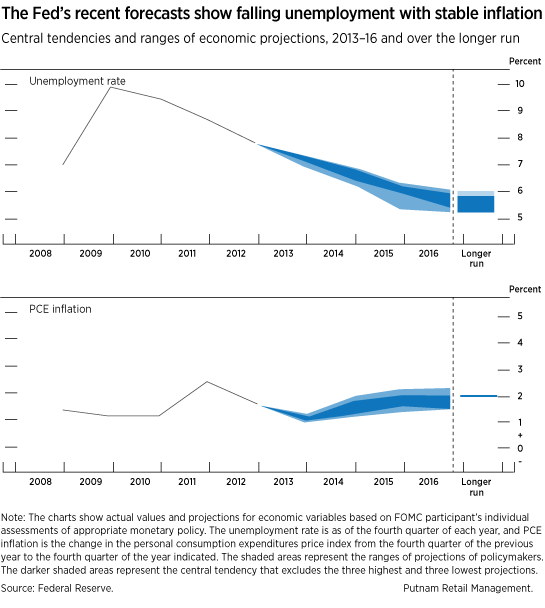

Today, when some economists at the Fed look at the structural and cyclical factors retarding growth in the labor supply, they believe that cyclical factors dominate. In other words, they believe that the normal relationships apply and that the drop in participation is cyclical. Once the economy starts to get going, by this thinking, a “normal” pattern of rapid job creation will occur. However, unemployment would fall only slightly, because young or discouraged workers will respond to the upturn and participate in looking for work again.

The policy prescription then follows. The Fed could keep monetary policy easy for quite a long time, since growth with high unemployment means no upward pressure on wages, which means no inflationary pressure.

If structural factors are more powerful, the Fed may be caught off guard

If the drop in labor force participation is structural rather than cyclical, then the Fed may have to raise rates a lot sooner. If the economy begins to accelerate and create jobs, yet potential workers choose to remain outside the labor force, they will not be counted as unemployed, and the unemployment rate will drop faster. In addition, firms will be forced to compete for available workers by bidding up wages. Resulting wage pressures would be inflationary, compelling the Fed to act.

It does not appear that the labor participation riddle will have a significant impact on rates over the next six months or so, because the unemployment rate is still relatively high, making it unlikely that a falling rate would generate inflation.

However, this grace period is fairly brief. The labor participation rate is likely to matter during 2014. The central question we are studying is how much of the drop in participation is cyclical and how much is structural. This question will have consequences for GDP growth and the yield curve.

284693

More in: Macroeconomics