- Europe’s economy could shrink by about 8% this year, nearly double the 2009 recession.

- Germany and France’s proposed €500 billion recovery fund will need unanimous approval.

- Italy and Spain, Europe’s hardest-hit countries, are pushing for more help from the EU.

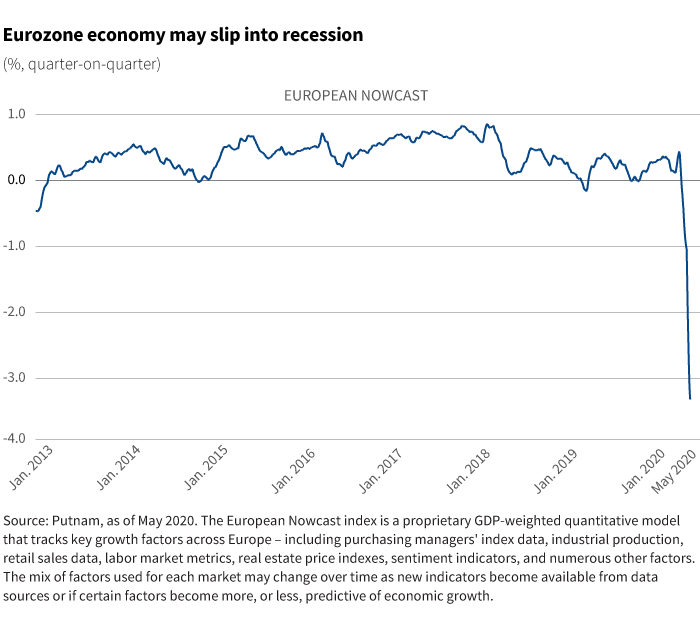

The economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic in Europe is shaping up to be terrible. The eurozone’s gross domestic product fell 3.8% in the first three months of 2020 from the previous quarter, and shrank by 14.4% on an annual basis, according to the European Union’s statistics agency. The European Central Bank (ECB) has flooded the financial system with cash through its bond-buying programs. In mid-May, Germany and France proposed establishing a €500 billion recovery fund to help the EU countries and industries worst hit by the pandemic. Still, the region’s economy will likely contract by as much as 8% in 2020, almost twice as large as the fall generated by the 2008 financial crisis.

German court takes aim at ECB rescue plan

Against this backdrop, a German court ruling on the legality of the ECB’s bond-buying program raises questions about the bank’s scope for action in the eurozone. The constitutional court ruled in May that the asset purchase program launched by the ECB in 2015 — and which continues — did not respect the “principle of proportionality.” It suggested policymakers did not properly assess the adverse effects of the initiative to prop up the eurozone economy. The court gave the ECB three months to justify its flagship stimulus scheme or the Bundesbank would have to drop out. There are two ways of looking at this decision: 1) this is the first decision by the tribunal that did not fully endorse ECB actions, and it came as a surprise; 2) the ruling has limited scope, and the ECB has some time to present arguments to the court.

We don’t see any threat to ECB actions from this legal decision in and of itself. It only addresses one of the ECB’s programs. Still, the decision could generate some volatility in coming weeks should the ECB ignore the ruling on the grounds that it is responsible to the European Court of Justice (ECJ) and not to national legal systems. The ECJ has determined the ECB is acting within its mandate. The Bundesbank is subject to the jurisdiction of Germany’s courts, and the end game here is that the central bank would be forced to partly withdraw from the euro system. While we don’t expect this to happen, the legal issue will have to be resolved at some point.

The court’s decision is a reminder of the underlying political stresses in the eurozone and the way they have been exposed by the pandemic and the economic weakness.

Nonetheless, the court’s decision is a reminder of the underlying political stresses in the eurozone and the way they have been exposed, yet again, by the pandemic and the ensuing economic weakness.

Eurozone’s north-south divide

A persistent fault line in the eurozone has been over fiscal policy; a group of northern, fiscally conservative states, led by Germany and including Finland, the Netherlands, and Austria (and non-eurozone member Sweden), have traditionally taken a different line on fiscal spending than the southern European countries that they have long viewed as profligate. This fault line has deprived the eurozone of the common fiscal policy that most analysts believe is an essential part of a successful monetary union.

The EU does respond to crises. The sovereign debt problem that followed the 2008/9 financial crises and recession led to the creation of the European Financial Stability Facility and the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) and established a clear pattern for dealing with economic difficulties in smaller peripheral economies. The ESM, which has large lending capacity, is based on the idea that countries get themselves into trouble, and that assistance has to be accompanied by domestic policy measures designed to “correct” the “policy mistakes” that led to the problems.

It is hard to argue that the economic consequences of the virus and the “stay at home” measures to control it are policy mistakes or the fault of the countries most affected. Italy and Spain, Europe’s hardest-hit countries, are pushing for more help from the EU. They have argued that it is time to revisit the case for a eurozone-wide fiscal mechanism with joint borrowing.

Finding some solidarity

At first, it seemed as though this latest chapter in the debate would end like previous chapters — with the conservative northern states continuing to shelter their taxpayers from taking on more obligations to fund the weaker, poorer countries of the south. But German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron proposed setting up the €500 billion recovery fund that would be funded (and leveraged) through the EU budget. Many observers considered this a breakthrough. It would create a new liability for Germany, which it previously resisted.

There is no doubt that this is a significant change. Germany decided the threat to the cohesion of the eurozone is large enough that it has to move decisively, and this is a step forward. What remains unclear, however, is exactly how large a step this is and how closely it will come to be the kind of common fiscal policy mechanism that outside analysts have long claimed is essential.

First, this is technically only a proposal from Germany and France. They are the most important countries in the EU, and they usually get their way. Still, the proposal needs to approved by all EU countries. The remaining members of the “frugal five,” now the “frugal four” (the Netherlands, Austria, Finland, and Sweden) are unhappy and are preparing a counterproposal. They will probably focus on limiting the size of this fund and reducing grant disbursements. The details matter. The commitment shown by Germany is important, but we need to see exactly what it amounts to.

Secondly, the amount of the recovery fund matters. The key problem with Italy is its size given its debt load and its history of extremely slow growth. Even generous terms on new EU funding won’t help Italy unless the amount of easy money is large. It is not at all clear that northern Europe’s taxpayers are prepared to support Italy on the scale that would make a real difference to Italy’s debt dynamics.

321756

More in: Macroeconomics,