- Parts of the Treasury yield curve have inverted as short-term yields drop less than long-term yields.

- Global growth risks, quantitative easing, and demographic changes make it easier for the yield curve to invert.

- We believe escalating trade tensions make a U.S. recession more likely.

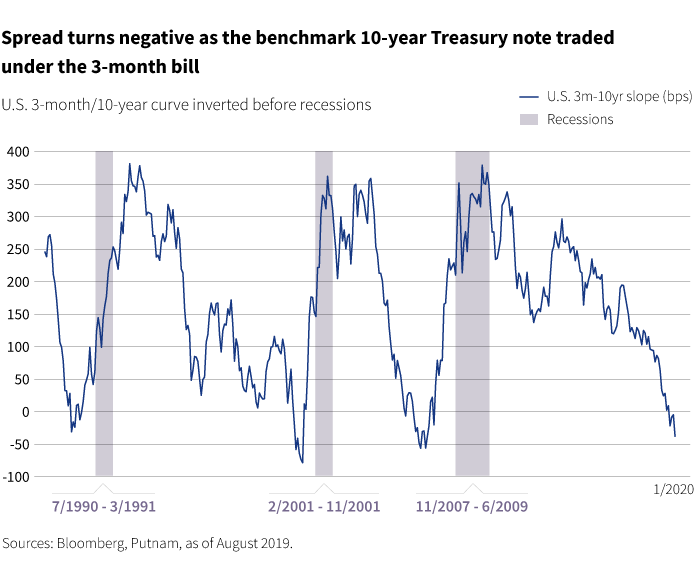

The yields on the 2-year and 10-year U.S. Treasury notes briefly inverted in August for the first time since 2007, rattling global financial markets. Meanwhile, the gap between yields on 3-month and 10-year Treasuries has been inverted since May. The yield curve is commonly considered a leading indicator of a looming recession. Are risky assets now vulnerable, or has the meaning of the yield curve changed over time?

We highlight three factors that have distorted the yield curve: low global growth expectations, quantitative easing, and demographic changes.

United States continues to outperform as global risks mount

At Putnam, we analyze the yield curve by using basic economic principles: demand and supply. Any term point on the curve is a price where demand and supply meet. In global financial markets, capital flows across borders. The supply of risk-free bonds (including Treasuries, German bunds, and Japanese government bonds) meets the demand for such bonds. At the very front end of the curve, central bank operations can overwhelm demand for or supply of short-term securities and determine interest rates. Central banks exert less influence as we move further away from short-term debt.

Market forces determine the long end of the curve. Investors often compare the yield, or the expected return, on risk-free bonds with returns offered by the other assets. If market participants’ return projections for risky assets are not high enough to carry the risk associated with them, they buy bonds. These purchases drive yields even lower. An inverted yield curve, therefore, indicates that the policy rate set by central bank is high relative to long-term global growth prospects, which is the key factor behind returns on risky assets. In a world with open capital accounts, the slump in long-term bond yields is more reflective of global growth concerns than future growth in the United States.

Quantitative easing distorts the information content of the curve

The world’s major central banks have mounted several quantitative easing (QE) operations since the global financial crisis in 2008, increasing their balance sheets. These large balance sheets make these institutions important agents in determining bond prices at the medium and long end of the yield curve. Since central banks are not price sensitive and their demand for government bonds is not based on their projected returns on other assets, large scale purchases through their QE program suppress long-term rates and distort the information content of the yield curve.

Secular rise in demand for government bonds

Higher demand for low-risk securities, such as Treasuries, has coincided with an increase in the global savings rate. Over the past 20 years, major developed economies have seen a rise in the share of population in the high-savings age group (30s to late 60s) relative to the total population. The preference for more savings cannot easily be overturned by low interest rates (that is, these savers are unlikely to consume more) since many of these savers are preparing for retirement. This structural change in the real saving–consumption balance is here to stay due to demographic trends and will continue to exert downward pressure on rates.

A recession remains a low probability

Based on the factors discussed above, an inverted yield curve can, at best, predict a lower rate of growth. But the curve alone cannot differentiate between lower growth (stagnation) and a recession. Historically, the U.S. economy has not had sustained periods of low but positive growth. When growth slowed materially, there was a recession.

Will it be different this time? The U.S. economy currently has more momentum — a strong labor market and firm consumption — compared with its counterparts. So, it is possible for the United States to avoid a recession with a lower growth path even as recessions or major downturns hit other economies. This is our base case scenario — that there will be volatility in financial markets, but U.S. assets will outperform international assets.

Although we don’t expect a recession in the United States, the escalation in trade tensions has raised this probability. If the global slowdown spills over into the United States, it is likely to be through the corporate channel. Therefore, we are keeping a close eye on corporate profits and business sentiment. We stand ready to adjust our portfolios in the likelihood of a recession.

318324

More in: Fixed income, International, Macroeconomics