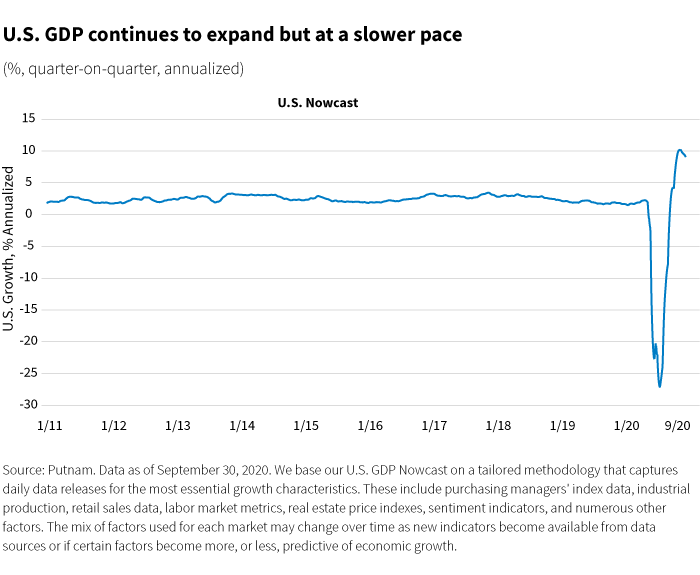

- Fiscal policy will likely be a key focus for investors after the November election.

- We expect the balance between taxation and spending will matter for growth and interest rates over the long term.

- Policy matters could hinge on control of the Senate, and the outcome depends on a few close races.

As the November election draws closer, it brings with it a new set of uncertainties. Recent national polls show former Vice President Joe Biden’s lead expanding over President Trump, who was diagnosed with COVID-19. Investors remain jittery about the future of American politics and policy, as well as the economy and the pandemic.

Shifting political landscape

The first presidential debate between President Trump and Joe Biden was chaotic. This year’s October surprise was news that Trump had contracted the coronavirus. Will this shift the election’s dynamics? First, the pool of undecided voters is not very large; most people have made up their minds about Trump, and the opinion polls have been quite stable. Biden’s lead in opinion polls is larger than Hillary Clinton’s during the 2016 campaign. Trump has lost some ground among people who supported him in 2016.

The big difference is that more voters will use mail-in ballots. There is the possibility that many ballots will be discarded. There could be arguments about mail-in ballot envelopes, signatures, and so on. The Republican Party has launched a massive fight to block changes to the voting process, including vote-by-mail. If the difference between Biden and Trump in a handful of key states is small, it could make a difference. We have seen this before. The Supreme Court effectively handed the presidential election to George W. Bush in mid-December 2000.

How will Trump’s COVID-19 diagnosis play into the campaign? Some of his supporters argue this gives him a chance to attract votes, although his health remains uncertain over the medium term. On the other hand, Trump has lost some ground in holding his signature campaign rallies and in-person fundraisers after being diagnosed with the coronavirus.

Reading opinion polls

What do the opinion polls suggest? With just three weeks to go before election day, and voting already underway in many states, President Trump’s support is falling behind his opponent’s nationally. Of note is that polling averages have been remarkably stable in recent months. Undecided voters comprise 6% of all likely voters, down from 11% in July. Current polling implies 352 electoral college votes for Biden compared with 186 for Trump.

The 2016 outcome has made people skeptical about polling. Beyond the polls, voter preferences are not fixed. The death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the controversy around her potential replacement, Amy Coney Barrett, have so far produced no discernable shift in polls. Plenty of news can happen in the final three-week sprint to the election. We could get some news on the development of a vaccine. Trump’s COVID-19 diagnosis may affect some voters. It may not take very much to push the odds in Trump’s favor, especially if there are polling biases.

Democrats hope to wrestle control of Senate

For policy matters, we believe control of the Senate will matter a lot, and that hinges on a few close races. The Senate is more delicately poised. It’s hard to be confident whether we will end up with the status quo, a small Democratic majority (1 vote) or a larger (2 or 3 vote) Democratic majority. Opinion polls show that Republicans will likely defeat the re-election bid of Alabama’s Doug Jones. On the other side of the ledger, the Democrats seem likely to win in Maine, Colorado, and Arizona. A few polls suggest Lindsay Graham’s South Carolina seat may be in play.

For policy matters, control of the Senate will matter a lot.

Based on recent polls, we believe the Democrats will gain a small majority in Senate. But that is far from being guaranteed. The size of any Democratic majority will matter for the policy agenda; Democrats would need a majority of 2 or 3 seats to advance some of their policies. Unified political control in Washington is a rarity, and if it happens, it’s not likely to last beyond the 2022 mid-term vote. There will likely be an aggressive push by the Democratic Party to take advantage of this two-year window for policy changes.

Much of this will have considerable impact on various sectors and not as much on the macro economy. Environmental policy is an example. Reinstating pollution controls on fossil fuels just puts the cost burden on the polluter and removes it from the public sector. It will affect the profitability of polluting activities. Reforms to health care will probably affect the relative profitability of insurers, drug companies, and care providers. A health-care system less tied to employment would probably increase the flexibility of the labor market and, at the margin, support growth.

Markets eye fiscal policy

We expect fiscal stimulus will be the main focus for investors after the vote. Full Democratic control would result in bigger fiscal spending to bridge a vaccine-led recovery, in our view. In the current economy, it’s hard to worry about the interest-rate effects of deficit spending. That is partly because we expect the Federal Reserve to adjust its quantitative easing program to offset higher debt issuance. Over the long run, though, an increased supply of bonds would push rates higher unless demand rises. That may be a challenge for the Fed, but not until later in 2021 and 2022.

It is becoming accepted wisdom that a Democratic sweep would increase the 10-year Treasury bond yield by about 50 basis points. This is partly due to lower political risk. Rising yields in the short term could affect the Fed’s determination to support the recovery.

Over the long term, the balance between taxation and spending matters for growth.

Over the long term, we believe the balance between taxation and spending matters for growth, and therefore for interest rates. It seems inevitable, in our opinion, that the tax burden will rise no matter which party is in control. Raising the tax burden in a way that is the least growth-unfriendly is economically easy, but it’s politically challenging. Reducing spending in a way that is the least growth-unfriendly is the same.

Given the U.S. elections, global economic conditions, and the global savings/investment balance, it’s hard to get excited about higher real rates; significantly higher nominal rates will increase inflation risks. Higher corporate taxes — virtually certain over the long term — would reduce after-tax profits and impact the equity market. That could ripple through asset markets in a way that may affect exchange rates and growth. But we believe the type and timing of tax increases that are under discussion is not likely to have major macroeconomic effects.

323560

More in: Fixed income, International, Macroeconomics