- A new U.S. coronavirus relief package remains elusive as impasse drags on in Congress.

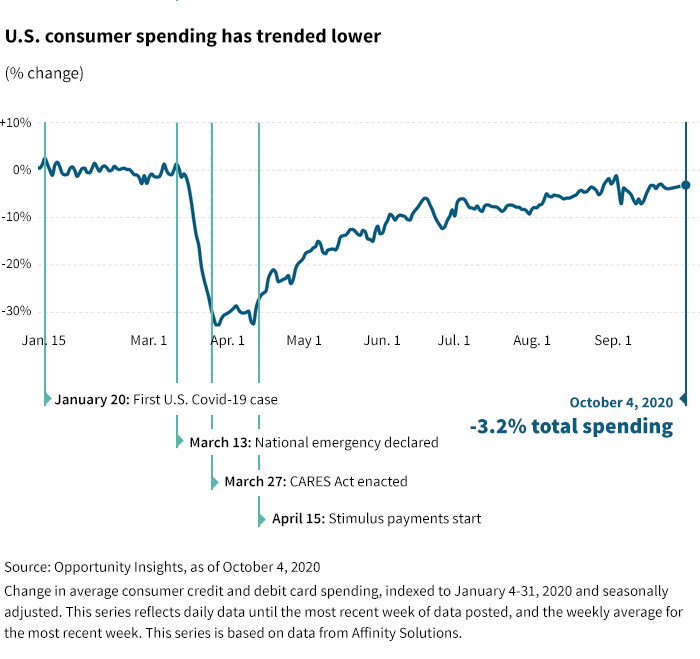

- We believe there are only downside risks to consumer spending in the fourth quarter.

- Further easing is likely in Europe and the United States, with the ECB closer to being the first to make a decision.

Global fiscal and monetary policies remain at the center of the debate over how to manage the economic recovery between now and the availability of a COVID-19 vaccine. The initial wave of the pandemic — and its economic effects — was met by aggressive monetary and fiscal policy responses. These played a key role in stabilizing the economy and financial markets. It is here that there are downside risks.

U.S. stimulus talks in focus

The U.S. elections in November matter, and the political atmosphere has been influenced by the death of former Supreme Court Justice Ginsburg and the looming confirmation of her replacement. But there is also debate over the next steps for monetary and fiscal policy, which will continue to play out after the election. The fiscal debate is over how much the government should do, and where it should focus its spending. As stimulus talks continue, there remain differences between the Republicans and the Democrats.

Democrats have been arguing for a large package, with funds directed to state and local governments, hospitals, and households, especially the unemployed. Their latest proposal was about $2.2 trillion. Republicans are divided, with some arguing there is no need to do more given the rise in the fiscal deficit and the ongoing economic recovery. Others are calling for a smaller package with most funds directed at households. Their latest proposal amounts to $650 billion, although President Trump has indicated he would go as high as $1.8 trillion. Republicans have also insisted on some form of COVID-19 liability protection.

As the election gets closer, the simple political theater of pose and counter pose becomes more important.

As the election gets closer, the simple political theater of pose and counter pose becomes more important. The prospects for a deal do not look particularly encouraging currently. If a deal is reached, it will be short term, and, deal or no deal, the issue will resurface after the election, in our view.

No silver lining in consumer spending

Politics aside, does the economy need more help, or is the recovery well underway with internal dynamics that will allow it to shrug off the fiscal position? This debate is going on in much of the world now because deficits have risen sharply and economies are growing, albeit not very quickly. The key question revolves around household spending.

We are rather pessimistic about the outlook for households because of some simple arithmetic. Two scenarios illustrate this math for the fourth quarter — one with generous unemployment benefits and a second round of stimulus checks, and the other with no income support. Under the first scenario, household disposable income could grow at an annualized pace of perhaps 25%. Under the second scenario, income could shrink at an annualized pace of 12%. We believe households would need to decide to spend or save. The savings rate has been volatile in 2020; it fell from 34% in April to around the mid-teens currently.

While households can use their savings to maintain spending growth, to do so they would have to be reasonably confident about the prospects for the labor market and for a reduction in the COVID-19 threat over the near term. That’s why we believe there are only downside risks to spending in the fourth quarter in the absence of a “Phase 4” fiscal deal and in the presence of a probable rise in COVID-19 risks as the weather cools.

Some households are keeping their consumption up by taking advantage of rent deferrals and eviction moratoria. This is not a lasting source of spending. It distributes distress around the private sector, and it’s a game of pass the parcel.

The latest labor market data provided some comfort to optimists and pessimists. The pace of job creation was weaker than expected, but a lot of this reflects oddities with government employment and the seasonal adjustment of teachers returning to school. Private sector employment grew, but the pace of hiring has slowed.

Years of rock-bottom interest rates

On the monetary policy front, we don’t expect to see significant changes over the short term. We haven’t had much more clarity from the Fed on what its new policy framework means beyond a long time with no rate hike. In August, the Fed announced that its new monetary policy will essentially abandon its strategy of preemptively lifting rates to head off higher inflation. The Federal Open Market Committee (FMC) does not appear to agree on exactly what the new framework amounts to. In the current environment, we believe the risks of a policy mistake are high. Fed officials have signaled plans to leave short-term rates near zero through at least 2023.

We haven’t had much more clarity from the Fed on what its new policy framework means beyond a long time with no rate hike.

The European Central Bank has started to worry a bit about the exchange rate of the euro. These concerns, however, will not be soothed by signs of renewed rises in COVID-19 cases in many countries and the resulting deterioration in economic indicators. Spain looks particularly worrisome, and it’s large enough to matter for the eurozone. The most recent inflation data was weaker than expected and strengthens the stance of the doves on the ECB board.

At the margin, some further easing is likely in Europe and the United States, with the ECB closer to making a decision first. German government bond (bund) yields have declined the most among the G-3 countries over the past month and are much closer to their lows of 2020.

323561

More in: Macroeconomics,