- Governments are trying to calibrate their policies to support growth as “fiscal cliffs” loom.

- The European Central Bank signaled plans to ease again in December amid potential economic weakness.

- The Federal Reserve is in discussions about adjusting its quantitative easing program.

The world’s policymakers are facing complex choices of when and how to expand their funding spigots amid a resurgence in the virus and renewed lockdowns. Governments have already spent trillions of dollars in pandemic programs in 2020 to rescue their economies.

Some countries move to avoid fiscal cliffs

In Europe, Japan, and those parts of the emerging-market countries where there is fiscal scope, governments are trying to calibrate their fiscal stances to support their economies. This is for the period until a vaccine makes it possible for a more complete recovery and try to minimize the effects of “fiscal cliffs” as earlier stimulus packages expire. In the global race to contain the pandemic, it was announced in November that the initial results of two vaccine trials have been extremely positive.

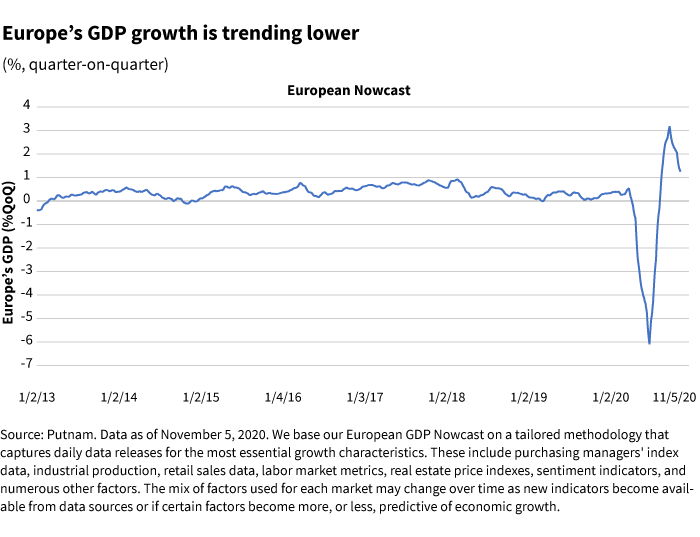

Countries such as France and the United Kingdom have reintroduced restrictions on mobility and on economic activities amid a second wave of coronavirus infections in Europe. For the most part, these restrictions are somewhat less onerous than those in the spring. Even with limited closures, however, we believe the euro area is heading for a double-dip recession. We forecast the economy will likely shrink in the fourth quarter of 2020. Unless there is a significant policy easing around the turn of the year, in our view there is a likelihood that first-quarter GDP will be zero or negative.

Against this backdrop, policy is already moving to respond; governments are being given free rein to adjust fiscal policy without regard to the rules that, in normal times, constrain public spending. Exactly how much more will be needed will depend on the course of the virus in the coming weeks. Germany, for example, announced a €10 billion package at the end of October for companies hit by renewed restrictions. These efforts are being supported by a European Central Bank (ECB) pledge to keep borrowing costs low and add stimulus.

In the United States, fiscal action was held up by the elections in November. Senate Majority Leader McConnell has indicated a renewed willingness to take up a possible fiscal measure. But he and Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi remain far apart on the cost. Presumptive President-elect Joe Biden has also said he wants to see an aid bill passed by year’s end. Given the election results, we believe any package will be small. It will help, of course, but it won’t materially shift the outlook for the U.S. economy in our opinion.

ECB is ready to inject fresh monetary stimulus

Central banks have remained active. The ECB has clearly signaled it will take easing steps in December to support the eurozone’s economy. The ECB’s key interest rate currently stands at minus 0.5%. Even a leading ECB conservative policymaker has indicated that a rate cut, deeper into negative territory, is under consideration. The Bank of England (BoE) agreed to increase bond purchases in November, while the Reserve Bank of Australia cut its official cash rate to near zero and announced a 100-billion-Australian-dollar quantitative easing (QE) program.

The ECB has clearly signaled it will take easing steps in December to support the eurozone’s economy.

In the United States, the election results mean there is likely a bit more weight on the Fed’s shoulders in the coming months. The Fed is in the midst of internal deliberations about adjusting its QE program in light of the risks to the outlook and the changing probabilities of fiscal support. We should expect a lot more tinkering in the next few months, but that’s all – tinkering.

The problem, of course, is that central banks are running out of ammunition. They are not completely out, but there isn’t a whole lot they can do and what they can do is not going to produce big effects in our view. Playing around with amounts of QE and the timing of QE flows, as the Bank of England did with its most recent announcement, sends a signal to the market, but we do not believe it is a particularly powerful one.

323946

More in: Fixed income, International, Macroeconomics